By Grace Gibson-Snyder

Source: Walnut Valley Water District

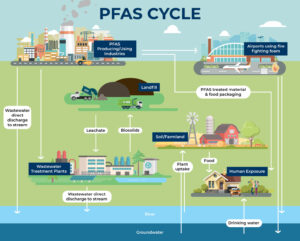

Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, abbreviated as “PFAS” and often called “forever chemicals,” are human-made chemicals that were first developed in the 1940s. There are literally thousands of types of synthetic PFAS chemicals, which makes it hard to gather comprehensive information about them. PFAS are widely used due to their oil- and water-resistant properties, and can be found in everything from makeup and waterproof clothing to nonstick cookware and firefighting foam.

Unfortunately, PFAS are also extremely toxic, even in tiny amounts. They are found in air, soil, and water. They bioaccumulate over time and take decades to break down; about 99% of Americans have PFAS in our blood.

Each person’s PFAS levels are different. Higher levels can be caused by living or working around PFAS contamination, whether in air, soil, water, or substances like firefighting foam. Higher levels are caused by exposure to some consumer products, like food packaging, waterproof clothing, and stain resistant carpeting. Consuming contaminated food and water raises PFAS levels, and about 200 million people in the U.S. have PFAS in their drinking water. Finally, levels tend to be higher in children and pregnant women because their food consumption is high in proportion to body weight, and thus proportionately increases their exposure. PFAS in our bodies may lead to decreased fertility in women, developmental effects in children, increased cancer risk, reduced immune responses, hormonal changes, and a higher risk of obesity.

Beyond the extremely personal impacts PFAS can have on our health, their impact on agriculture should be of particular interest to Montanans. Because PFAS often end up in water supplies, they accumulate in wastewater treatment plants. The process by which the water is treated does not remove the PFAS, and the wastewater solids still contain high levels of forever chemicals. When the solids are recycled as biosolids to be used as fertilizer, the PFAS contaminate our soil and water, and ultimately, our food supply.

Other sites of concern in Montana are military facilities. Military facilities are prone to PFAS contamination largely due to their use of firefighting foam. The Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has designated five sites as PFAS Sites of Concern: Malmstrom Air Force Base, Helena Army Aviation Support Facility, Fort Harrison, Montana Air National Guard Base in Great Falls, and the Former Glasgow Air Force Base.

One would think that, given their huge presence in our lives and their health harms, PFAS would be tightly regulated. Unfortunately, regulation has been limited. Until the late 1990s, information about their toxicity was hidden from the EPA and the public; subsequently, the EPA has been stymied by political and industry influence preventing regulation. Although the EPA has released two action plans to address PFAS (in 2009 and 2019), few actions were taken until the EPA released the 2021 PFAS Roadmap, which contains proposed timelines for PFAS research and regulation. (Read more about EPA’s actions at www.epa.gov/pfas.)

As of this writing, PFAS are still not regulated under any federal environmental statute. However, the EPA has proposed three actions to begin regulation:

1. In March 2023, the EPA proposed to establish legally enforceable levels for six PFAS found in drinking water.

2. EPA’s Emerging Contaminants in Small or Disadvantaged Communities grant program will provide $2 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to communities to address emerging contaminants, including PFAS.

3. In April 2023, the EPA asked for public comment on its proposed designation of several PFAS types as hazardous substances. This designation would fall under the Superfund law (a.k.a., the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, or CERCLA) and would allow EPA to investigate and clean up highly contaminated sites across the country. Critics say that by only designating a few PFAS out of the thousands of types as hazardous substances, this regulation would simply encourage polluters and manufacturers to shift towards closely related but less-studied alternative PFAS. Instead, they say, the EPA should go further to include the entire class of these forever chemicals in its Superfund program.

MEIC’s friends at Earthjustice are tracking EPA’s 2021 Roadmap at www.earthjustice.org/feature/pfas-chemicals-epa-roadmap.

Montana DEQ has added two PFAS to official groundwater quality standards and has monitored water sources for PFAS. In 2020, it developed a broad plan to address PFAS. Further action based on this plan “will be determined… based on agency/stakeholder resources, availability, expertise, and regulatory authorities.” Read more at www.deq.mt.gov/cleanupandrec/programs/pfas.

Thanks to Christine Santillana at Earthjustice for her expertise and contributions.

This article was published in the September 2023 issue of Down To Earth.