By Ann Schwend

Developers have been exploiting the exempt well loophole in Montana for years. Image from Gallatin Local Water Quality District, 2010.

Developers have been exploiting the exempt well loophole in Montana for years. Image from Gallatin Local Water Quality District, 2010.

Water and land use are inextricably linked, and where we build matters, especially for our water future. In many cases, water is, or should be, the limiting factor on whether a development is appropriate in arid, dry, and water-constrained Montana. Water “rights” create a complex tapestry of regulation and control. And like in a tapestry, loopholes can have devastating effects on water quantity, water quality, and the battle against sprawl.

Current Montana water laws are complicit in driving subdivision sprawl, especially just outside of fast-growing cities. Exempt wells – or those water uses that are “exempt” from the traditional permitting process – were originally intended to provide small amounts of domestic and livestock water where public water systems are not available. The intent was to have a simplified process to provide small amounts of water without a complex and cumulative analysis of potential impacts to other water users, which seems appropriate in very rural areas. Unfortunately, this simplified process has created a loophole that is now commonly used for subdivision development and having a profound effect on open spaces, water resources, and sprawl.

In many parts of Montana, we already recognize that there is not enough water to meet current legal demands, so the state has “closed” many areas to permitting new surface water rights. Since Montana water law also recognizes that surface water and groundwater are connected, the surface water closures make it extremely difficult to get a new groundwater (well) permit in an administratively-closed basin. Thus, new developments face many challenges to getting a water right if they want to build a public water system for a subdivision outside of a municipal area. This means the default mechanism is to rely on exempt wells for household and landscaping water supplies.

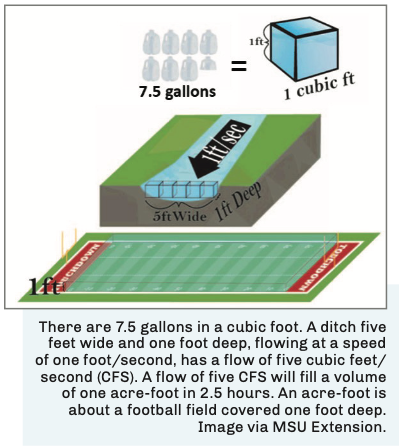

However, there are many problems with using exempt wells to supply water for subdivisions. Since these wells are exempt from the detailed level of environmental analysis that a typical water permit application requires, it is difficult to measure the cumulative impacts on surrounding water supplies. An individual homeowner can simply drill a well and then file a simple notice with the Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC). DNRC reviews the application and issues a certificate defining the rate and volume allowable for that well, which cannot be greater than 35 gallons/minute and not more than 10 ”acre-feet” per year. This is a lot of water: 10 acres of water at one foot in depth. However, most of the time, there are no requirements for the homeowner to measure or report on actual usage, so the individual and cumulative impacts are difficult to ascertain.

In many cases, the exempt well provision is the leading cause of sprawl in Montana’s fastest growing areas. If a development is located in a closed basin and the developer cannot acquire an existing water right or hook into an existing public water system, they default to using the exempt well provision. Some developers are willing to drill the wells for each of the lots before selling them, but they are not required to do so, and many don’t. Some developers might drill one well and then put in the infrastructure to deliver water to each of the lots (as proposed in HB 435, Rep John Fitzpatrick, R-Anaconda). Or the developer can pass the expense (and confusion) onto the new unsuspecting lot owners to independently drill their own wells. In each of these situations, the total amount of water allowed for the proposed subdivision is 10 acre-feet, regardless of how many individual wells are installed.

In the situation above, the cumulative amount of water for the subdivision is defined under current rules as a “combined appropriation,” meaning that all of the wells in the subdivision are presumed to be pumping from the same aquifer. This definition was reinstated following a lawsuit in 2014 with the intent of protecting existing water users and tightening the exempt well usage. While the definition closes the loophole to some extent, when reviewing a subdivision application, DNRC can only determine the legal availability of water for that specific project area, without due consideration of the impacts to surrounding water users. HB 642 (Rep. Casey Knudsen, R-Malta) seeks to nullify the combined appropriation language and expand the amount of water that could be used by exempt wells in subdivisions. It would also be retroactive and allow users to modify their pre-2014 applications, further complicating an already messy and unmitigated issue. MEIC opposes this bill.

Using exempt wells to provide water for rapidly expanding subdivisions creates multiple problems. As with any exemption, these wells should be the exception, not the default. The individual wells are a key factor in encouraging sprawl. If each lot is using an individual well, they also often have their own septic tank and drain fields as well. The Montana Department of Environmental Quality has minimum separation requirements between those systems on the homeowner’s lot, as well as setbacks from neighboring properties. These setbacks require at least one acre per lot, which increases the amount of land needed for each individual home and water/wastewater system. Multiple septic systems also increase the potential for contaminating shallow groundwater and areas where local wells may be pumping water. But the biggest concern is that these individual wells and septics are requiring more land than most homeowners can practically manage, and spread the development over much larger areas. Sprawl by definition.

As the demand for more homes increases and more people opt to live in rural subdivisions, do communities really want to consume large swaths of valuable agricultural land and open space, while also increasing the reliance on vehicles? Or should communities invest in their collective future, minimize footprint, and find ways to accommodate more people within existing urban areas, where sustainable neighborhoods can thrive? Let’s rethink existing spaces, shore up public infrastructure, and provide adequate and well-monitored public water and wastewater systems. Let’s reduce the loopholes for water use in developments that encourage sprawl across the landscape.

This article was published in the March 2023 issue of Down To Earth.