By Ann Schwend

We all need water to survive, and it is certainly much more convenient if it is piped directly into our homes rather than hauling it one bucket at a time. But just how clean and secure are those supplies? The answer may depend on whether that water is coming from an individual domestic well or from a public or municipal system.

In Montana, most of the new subdivisions that are being built outside of city limits (and out of range for public water utilities) rely on individual domestic wells for water supplies. This is occurring for a variety of reasons, but mainly because putting in a public system is a big investment and requires a permitted water right. Obtaining a water right permit is costly, time-consuming, and can be very difficult. Many of our fastest-growing communities are located in basins that are administratively or legislatively closed to any new surface water rights because there are more water rights than water that is actually, physically available (“over-appropriated”). Because a public water system requires a legal water right, it makes it extremely challenging for housing developers, especially in a closed basin. This leaves few choices and drives developments to depend on “exempt wells” in order to provide water for the new homes. What was meant to be a minor exception to the water rights system is now the default method used to bypass it altogether.

So, what exactly is an exempt well? The definition has gone through many legal and statutory changes, but suffice to say, it is a domestic or stock water well that is exempt from the traditional water right permitting process. These small wells pump water at less than 35 gallons per minute to a maximum of 10-acre feet per year in total volume. Basically, the landowner drills a well, files an application, and the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC) will issue a certificate of completion for that well. This simplified process is not the same as the full permitting process to get a traditional water right permit. The full permitting process requires an in-depth analysis of legal and physical availability and cumulative impacts, and sufficient notification to potentially affected water right holders.

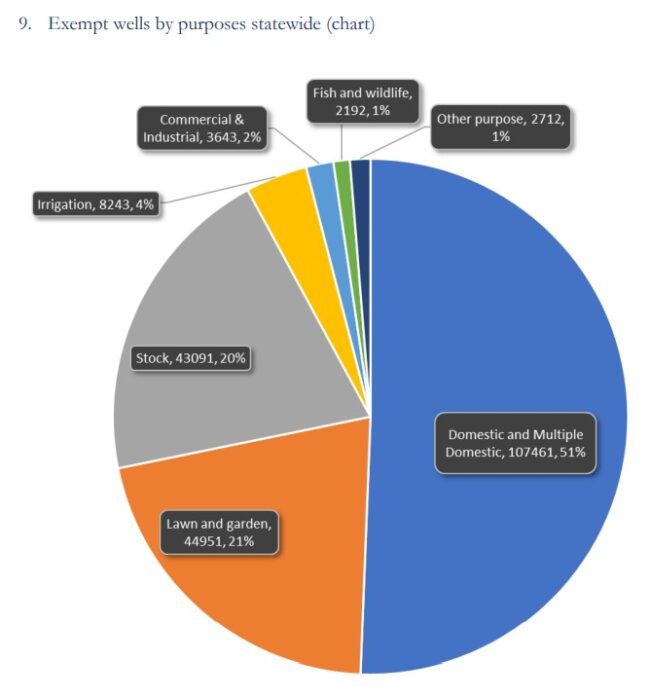

As of September, only about 25% of exempt wells in Montana are for stock or irrigation.

Chart via DNRC.

The original intent of the exempt well provision was to provide water for rural homesites or livestock. Unfortunately, this exemption is now creating a problematic loophole as more and more developments rely on this system for their water. Building entire subdivisions and ignoring the cumulative impacts of hundreds or thousands of wells is creating an unmitigated, unmonitored trainwreck. While domestic or household water use is not “consumptive” (the water returns to the system via a septic drain field), most households have some outdoor landscaping and lawns, which is very consumptive. Additionally, as communities grow and multiple subdivisions locate in close proximity, there is an increased risk of drawing down the aquifer, especially during the hot summer months. Recall that when DNRC reviews a proposed subdivision, it does not analyze the cumulative water resource impacts or physical availability of multiple individual wells outside of the proposed project area. Since exempt wells do not require the full water permitting analysis, DNRC only reviews each proposed project independently, without consideration of how the new wells will impact existing water rights and surrounding wells.

Another issue with exempt wells is that homeowners often don’t realize the potential vulnerability of their water quantity or quality. Long term monitoring and maintenance of individual wells are the responsibility of the private property owner. The homeowner has the well drilled, maintains the pump, protects the well head, and (should) check annually for contamination in the well. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, more than 43 million Americans rely on private wells, and federal experts estimate that more than a fifth of private wells have contaminant levels that are considered unsafe. It is especially important to monitor wells in areas with high concentrations of older individual septic systems, which may not be designed or maintained to filter out bacteria, nitrates, pharmaceuticals, minerals, or forever chemicals (PFAS). Additionally, if aquifer levels change due to drought, new developments, or changing land use practices on neighboring properties, then it is the homeowner’s responsibility to drill a deeper well. There are no guarantees that groundwater will continue to remain at current levels, especially as we continue to put more unmonitored “straws” into the system and change land use and irrigation practices, all without consideration of the interconnectedness to the diminishing aquifer.

On the other hand, homes located on municipal or public utility systems have a larger degree of certainty that water will be supplied to their homes. The responsibility for securing and effectively delivering water lies with the public works department, and not the homeowner. The water is also treated and tested regularly for pollution or pathogens. Homeowners pay for the amount of water that is consumed through monthly bills, but they don’t have to stay up at night worrying about pumps going out, declining aquifer levels, or unsafe drinking water.

While it may be easier, or less costly, for the developer to build without providing a water supply system, it is not necessarily less expensive to the homeowner. We cannot continue to behave as if water is an unlimited resource or that exempt wells don’t impact existing water users or everyone’s right to clean water. Changing land use and a rapidly changing climate will only increase the supply and demand imbalance, and we need a system that accounts for all water use, protects water right holders and provides homeowners with a defensible water right. It is time to reconsider how to adequately provide water for new development through a new permitting system that considers cumulative impacts and plans for future growth. Too many straws in and out of the same system is already causing a noticeable difference in overall water levels and quality. Something needs to change.

This article was published in the December 2023 issue of Down To Earth.