By Ann Schwend

The earth is warming. Humans — and our lifestyle choices, large living quarters, electricity consumption, and personal vehicles — are responsible for emitting much of the carbon pollution that is driving that change. Making better individual choices can be part of a climate solution, but how development occurs is an important part of the puzzle. Poor planning can significantly increase carbon emissions, and thoughtful planning can help cities grow with fewer harmful impacts to our climate. While MEIC will continue working toward high-level, high-impact climate solutions, local solutions can also add up, especially when it comes to development patterns and local household carbon footprints (HCFs).

Increased carbon footprints are accelerating climate change, so how we develop our communities really matters. According to the Brookings Institute, U.S. urban land area grew 1.7 times faster than population growth between 1960 and 2010. This data indicates that a much larger percentage of people are living in locations that require more driving, increasing Americans’ daily travel mileage by 85%. We have created and encouraged a shift from walkable city living to a suburban car culture. Studies have consistently shown a lower HCF in urban areas as compared to outlying suburbs.

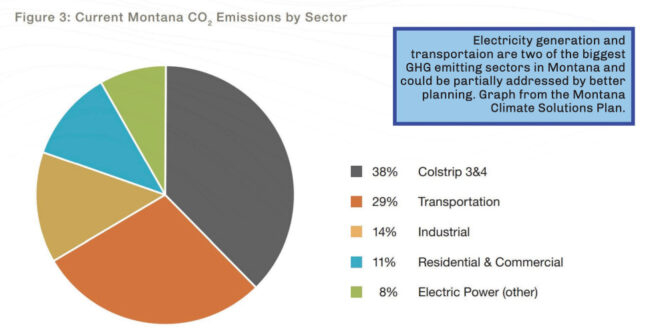

In Montana, due to limited public transportation and longer commute times, car culture is a driving factor in higher carbon footprints, with vehicle exhaust accounting for the largest percentage of carbon emissions. Moving further away from city centers, the HCF tends to increase because homes are often larger, single-family units and the residents drive more. Even if a rural resident drives an electric car, runs energy-efficient appliances, and has a solar-powered home, a 20-mile commute likely contributes more carbon than a resident in a duplex or apartment in town. Quite simply, in order to address the climate crisis, we must change our unsustainable land use practices by building human-centered neighborhoods that minimize car culture and consume less energy.

Development patterns also impact the local hydrology. Increased temperatures mean that snowpack is melting earlier each spring. If the majority of the annual water budget falls as snowpack, and then comes out in a spring flash, it is vital to capture that water when it is available. Allowing a river to spill over its banks and saturate the floodplain can function much like a sponge to slow down high spring flows, percolate into the shallow aquifer, and slowly release critical late summer return flows to the rivers and streams. If structures, homes, and roads restrict the floodplain, much of the annual available water flows by and the opportunity to store snowmelt is lost until next season.

Traditionally, communities have built levees to protect themselves from floodwaters, but channelizing the river may actually increase downstream flooding. Confining a flooding river increases pressure and velocity, much like a firehose, so that once past the levees, the downstream communities are greatly impacted. While it probably isn’t feasible to move entire cities out of the floodplain, it is possible to better incorporate water resource planning with land use planning and minimize future building in locations that aren’t suitable. Flooding doesn’t have to be a natural disaster but could be an opportunity to bank water and recharge aquifers. Current floodplain management is all about reducing the risk for man made structures. We should rethink this approach and instead identify and minimize development in areas where flooding is reasonable to recharge the system and reduce downstream flooding.

It’s important to consider the causes and effects of a changing climate. Changing precipitation patterns impact future water supplies and, as Montana warms, summers become longer and drier, dramatically changing water use and availability. Each of these factors creates a bad feedback loop for maintaining sustainable communities. It is important to consider historic development patterns, learn from the mistakes, and plan for a hotter future with a limited water supply.

It’s important to consider the causes and effects of a changing climate. Changing precipitation patterns impact future water supplies and, as Montana warms, summers become longer and drier, dramatically changing water use and availability. Each of these factors creates a bad feedback loop for maintaining sustainable communities. It is important to consider historic development patterns, learn from the mistakes, and plan for a hotter future with a limited water supply.

We simply cannot reach emissions reduction targets unless we reconsider our growth and development patterns. Addressing the drivers of climate warming is paramount, such as reducing vehicle emissions by encouraging more development in walkable urban areas and climate conscious lifestyle choices. We also need to locate development more appropriately and adapt to changing hydrologic regimes. These changes can start in our individual homes and how we plan, locate, and build our communities.

This article was published in the December 2023 issue of Down To Earth.