by Laura Collins

Montana is facing a growing and increasingly dangerous wildfire threat. Fueled by climate change, population growth, and rapid development in high-risk areas, wildfires are becoming more frequent, more intense, and more destructive. As more homes are built in Montana’s wildland-urban interface (WUI) — the zone where human development meets wild landscapes — the risks to life, property, and the state’s financial future grow with each passing year.

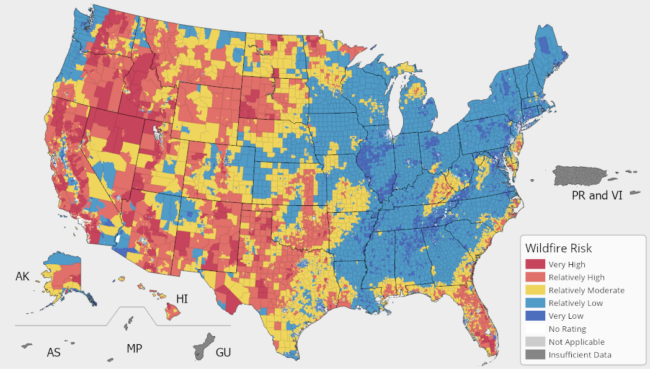

Wildfire risk in Montana needs to be considered in where and how we build. Image via FEMA.

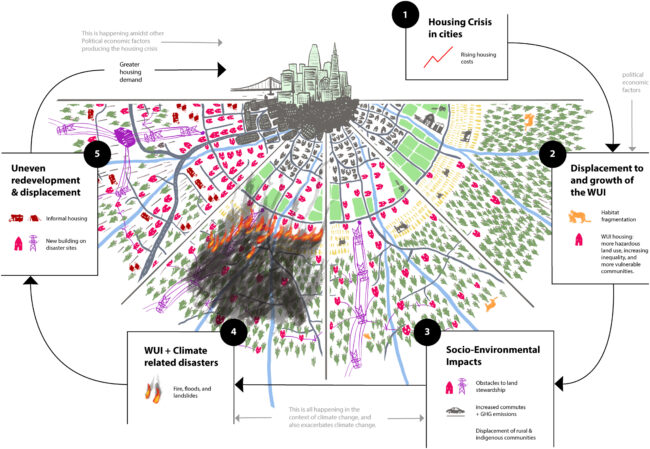

Montana’s wildfire risk is as much a climate issue as an urban housing policy issue. The state’s rapid population growth and urban housing shortages are driving both affluent “amenity migrants” and lower-income “affordability migrants” to settle in the WUI. Many rural areas offer relatively affordable housing and fewer land-use restrictions compared to many urban centers, creating an incentive to develop in high-risk areas. These remote developments often lack access to emergency infrastructure, such as adequate water for firefighting. Critically, homes built to modern wildfire safety standards are 40% less likely to be destroyed than those built without such protections. Yet, wildfire damage in these areas disproportionately affects the vulnerable “affordability migrants” who — unlike the affluent “amenity migrants” likely building second, third, or fourth homes — have fewer resources to protect their homes and recover from damages.

WUI development is not only the leading cause of wildfires, but as it expands, it also worsens the fires themselves, and the cost of our inaction is staggering. In 2023, Headwaters Economics reported that an astonishing 87% of wildfires from 2010 to 2020 were caused by human activity, and estimated that 50-95% of the state’s $2.5 billion spent annually on wildfire suppression goes toward protecting residential structures. Yet, from 1990 to 2020, the number of new homes built in wildfire-prone areas of Montana doubled. During that time, Montana lost more than 1,400 structures to wildfires. Yet, subdivisions continue to be built in high-risk zones without proper planning, oversight, or fire-resilient infrastructure. This is due to the lack of any clear, enforceable wildfire safety standards in Montana’s current legal framework.

Image via PNAS.

Despite these damages and mounting dangers, Montana remains one of the few Western states without a comprehensive, statewide set of WUI zoning and building standards. While the state has developed an impressive wildfire risk map through its Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC), it has not created the legal or regulatory framework necessary to act on that data. Rather, Montana’s current approach to wildfire risk management is dangerously inadequate.

The state has adopted a heavily diluted version of the International WUI Code, deliberately omitting provisions such as structure density, water access, road requirements, and ongoing maintenance requirements. In fact, state law explicitly prohibits local governments from denying development based on its location in the WUI or requiring fire-safe building material and techniques in zoning regulations. What’s left for communities are optional, half-baked guidelines, limited funding for landowner incentives and education programs, and overly complicated land-use laws that, too often fail to suffice. As a result, even counties and cities that want to take action find themselves hamstrung by limited authority and overly-complex procedures. It’s no wonder so few have bothered to try.

We need a statewide WUI code, yesterday. MEIC is working to support an important legislative interim study on increasing wildfire safety to demonstrate the need to tackle this problem sooner rather than later. Montana has a chance to learn from other states and act before it’s too late. Washington, for instance, has adopted the full International WUI Code and provides state-funded assistance to help local governments implement wildfire safety measures. The Montana legislature has the power to do the same.

By using the DNRC’s wildfire risk maps, Montana must adopt mandatory wildfire safety standards that account for location, density, construction materials, landscaping, water supply, and road access for all development in the WUI. Additionally, local governments need to be given discretion to adopt higher standards for wildfire protection to manage unique local hazard conditions. Jurisdictions should then be supported by state-level funding and technical expertise to implement and enforce WUI regulations. Finally, the link between urban housing shortages and WUI development must be addressed through robust policy changes that will meaningfully improve sustainable housing options and discourage further sprawl into high-risk areas.

MEIC is working to promote responsible WUI policy. Given the mounting stakes, we can’t afford inaction any longer. Responsible WUI policy would grant all Montana communities, especially those at greatest risk, access to tools and support needed to grow safely. But this will require centralized rulemaking and enforcement, dedicated funding and technical support to build local capacity, incentives for retrofitting existing homes in high-risk and socially and economically vulnerable communities, and integration of wildfire planning with broader affordable housing and climate policy.

Montana’s current approach to wildfire risk is failing. Wildfires are becoming more common, more destructive, and more expensive. Housing pressure, climate change, and population growth are converging in dangerous ways. The solution is not simply to stop building, but to build smarter. Mandatory wildfire safety standards will not only protect Montana’s homes and landscapes but also its people, economy, and way of life. By strengthening both fire-safe development standards and sustainable urban housing policy, Montana can become a national leader in climate-smart growth. MEIC is working to make that happen.

This article was published in the September 2025 issue of Down To Earth.