By Ian Lund

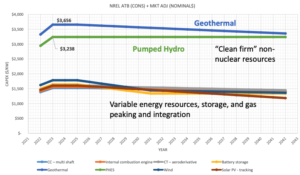

NorthWestern Energy’s estimates for what it would cost to develop various energy resources.

NorthWestern Energy’s estimates for what it would cost to develop various energy resources.

NorthWestern Energy is developing its latest Resource Procurement Plan, set to be finalized in December. This document is the end result of a reliability and economics planning exercise that Montana electric utilities are required to conduct every three years.

The planning process begins with the utility evaluating its generation resources against forecasted load growth (energy consumption). When long-term planning, the utility’s chief concern is reliability of its energy resources, rather than sustainability. The utility must have enough generation resources in reserve, such that it can always provide electricity to customers and avoid blackouts. This is known as resource adequacy planning. When power plants close and population and economic growth demand more energy, utilities may find that they do not have enough resources to meet demand. This is known as a capacity deficit.

Once the capacity deficit is identified and quantified, the utility needs to figure out how to close the gap. Computer modeling software evaluates what resources would be most economically efficient to meet a utility’s projected needs. The model can select from a variety of resources, including wind, solar, battery storage, natural gas, geothermal, hydro, and — new this year in NorthWestern’s analysis — nuclear, in the form of small modular reactors (SMRs). For each resource, the utility inputs into the model assumptions about how much the resource will cost to build and operate, and how much it can rely on each resource during events of peak energy demand.

There are two ways to align supply and demand: increase the supply by building new power plants (what NorthWestern traditionally wants to do) or decrease demand (what it ought to do). However, NorthWestern continues to ignore ways to reduce electricity consumption through either energy efficiency programs (to reduce the total energy used on a day-to-day basis) or through demand-side management programs, which reduces the amount of energy used during peak events. Energy efficiency and demand side management are two inexpensive methods utilities commonly use to help decrease electricity demand and avoid the need for new, expensive power plants. NorthWestern is even ignoring the Public Service Commission’s criticism of its previous plan by refusing to analyze buying power from companies that own resources that are already built and ready to deliver power.

We have been asking NorthWestern to model the closure of Colstrip Units 3 and 4 in its resource plans for the last two planning cycles, and it appears that the winds of change are finally lifting their sails. The 2022 Resource Procurement Plan will include three scenarios in which the Colstrip plant is retired: in 2025, 2030, and 2035. Given that closure is likely to happen in the near future, this modeling is overdue. While it is a relief to see Colstrip plant closure considered, closure means that 200 MW will be taken offline and need to be replaced. In two “sensitivity” runs, the utility will consider the economics of replacing the Colstrip plant with SMRs. Another sensitivity run will add the social cost of carbon to each resource, which will require consideration of the true costs of fossil fuels such as methane gas and coal.

Supply chain woes and inflation have increased the projected cost of all generation technologies, but solar, wind, and battery storage were hit harder than their fossil fuel counterparts.

MEIC will continue to participate in NorthWestern’s process to develop its new plan and argue for robust modeling of a broad mix of clean energy resources. NorthWestern’s commitment to a clean energy system needs to be more than just a PR campaign. Planning for a clean energy future is an essential first step in that direction.

Sign up for our Action Alerts list for ways you can provide input and get involved in this process.

This article was published in the June 2022 issue of Down To Earth.