This summer, I traveled across parts of central and eastern Montana to visit both long-time and newer MEIC members, and I want to share a few things I learned.

After a couple of weeks on the prairie, it’s clear that Montanans across the state are fighting many similar battles. From managing limited water resources to pushing against extractive industries to finding solutions using local knowledge, more unites us than divides us in the Big Sky State.

Medicine Lake’s disappearing shoreline is a result of aridification.

Medicine Lake’s disappearing shoreline is a result of aridification.

Water is Life

Communities in the far reaches of eastern Montana don’t have unlimited access to clean water for irrigation or drinking water, and it’s a reminder that people have been living in these places with limited water since before Montana was a state. The climate crisis is intensifying aridification (the process through which a region becomes drier) and increasing the frequency and intensity of droughts and wildfires, alongside a decrease in available clean water.

Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge is an important asset in northeastern Montana. One of the largest bodies of water in the area created from historic glacial activity, this lake was important for the first people of this land and remains important today. Its current water levels rely on two area creeks, summer rainfall, and snowmelt. There are numerous wetlands that are crucial for migrating birds in the area. However, over the past several decades, warming temperatures and decreased precipitation have lowered the area water levels, including in the lake itself, to concerning levels. Our eastern members say they have witnessed notable changes to the lake in their lifetime. With an average of fewer than 13 inches of rain per year, one could speculate how many consecutive years it might take to replenish the lake water.

While this sounds like an extreme example, I learned from every single community I visited that water quality and water quantity are often top concerns. The climate crisis could make it much harder for Montana communities to be resilient, and ecosystem changes are already being seen in real time all across the state.

Pollution from excess nutrients, resource extraction, and other dirty industries have long impacted water, but the cost of maintaining and improving water infrastructure without an accompanying adequate source of revenue is impossible for most communities. What’s even less clear is exactly how decisions from state legislators addressing sustainable planning, water quantity and quality, and ecological changes due to the changing climate will directly impact local communities and governments. Combined with the extreme recommendation for deregulation, it’s apparent that state and local policies are intertwined and interdependent, and the future of Montana’s water is truly at stake.

The American Prairie Reserve is beautiful and contentious in parts of Central and Eastern Montana.

The American Prairie Reserve is beautiful and contentious in parts of Central and Eastern Montana.

Crypto Infiltrating Under the Radar

Montana is no stranger to extractive industries that temporarily benefit nearby communities and leave behind long-term health and safety risks. There is a storied history of extended impacts to air quality and water quality and quantity from the moment oil, gas, and minerals are extracted through the process of transporting them to using them at generating stations or in homes.

However, there’s a new extractive industry that is bringing no benefits to Montana communities.

Along the North Dakota border, there are numerous cryptocurrency data center operations hiding in plain

sight on oil and gas well pads. More accurately, I heard the cryptocurrency operations before I saw them. The operations have massive fans which can be heard roaring across the landscape to cool the computers that are “mining” for digital currency.

MEIC has written extensively about cryptocurrency operations and how they threatened the quality of life and clean energy goals in Missoula County, revived a coal plant in Hardin, and continually greenwash the impacts of gluttonous energy consumption, such as a proposed massive solar array in Butte that would solely power a crypto facility. Despite some arguments to the contrary, the crypto industry is actually drawing out the clean energy transition to make a few rich people even wealthier by enabling more fossil fuel extraction and consuming clean electricity that could otherwise power homes and businesses.

The companies that run these facilities claim to be largely powering their operations with methane gas that would otherwise be flared. The fossil fuel industry erroneously claims that it’s not possible or profitable to capture and use flared methane gas for electricity, yet some are praising cryptocurrency operations as being a climate solution because they’re consuming methane gas, a very potent greenhouse gas. In reality, these companies are: creating a new demand for methane gas; releasing high volumes of greenhouse gases (when methane is flared, it releases both carbon dioxide and uncombusted methane); wasting gas that can be captured and used for societal necessities such as heat; and creating staggering climate impacts with the tremendous amount of energy needed for crypto mining. And to add insult to injury, most of the facilities were still flaring excess gas.

Once I learned what to look and listen for, I kept finding these facilities. The number of data centers was surprising, with sometimes as few as two or as many as eight on one well pad. The incredible volume of noise that the fans produced makes one wonder: how could anyone live near them? What is the impact on the quality of life, health, and economy from constant truck traffic transporting ??oil on the gravel roads leading to the facilities, in addition to the added noise pollution from the cryptocurrency facilities? True to the history of extractive industry in Montana, local communities will continue to bear the brunt of all the associated negative impacts of boom and bust industries while the profits go elsewhere.

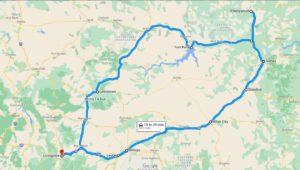

Melissa’s route through eastern Montana.

Melissa’s route through eastern Montana.

Local Solutions Under Threat

As a statewide nonprofit, many of the issues that MEIC works on deal with statewide policies, especially on issues that impact water quality and unfettered development. But what works for cities such as Helena, Billings, and Kalispell doesn’t always work for places such as Glendive and Miles City. Local communities often have solutions to address their unique needs.

While most of the attention about housing has been focused on a handful of western cities, there is concern across the prairie about housing affordability and availability, maintaining clean water, and rural water availability where it’s already quite arid. While a statewide mandate to promote housing development or water conservation can seem like a good solution, these cities are experiencing very different aspects of the same issue.

Western Montana is struggling to build enough houses to keep up with demand. Eastern Montana can’t always get builders. For example, some eastern Montana MEIC members have been working to get solar panels on their property for years, but they aren’t able to get return calls from solar developers willing to travel east. There is so much demand for work in the western part of the state that doesn’t require travel. The current promoted solutions don’t even begin to address the challenges of eastern Montana.

In addition, some in the state are calling for statewide deregulation of zoning laws to “open up” land for development in cities. But deregulating a map doesn’t reflect reality, and many small towns are nestled into unique topography or have limited water supplies that would make them expensive to develop. A statewide mandate about housing could be impossible for some Montana cities to fulfill.

In many cases, it’s most effective to empower local people and governments to seek solutions for their own communities while ensuring there are state-level protections for issues such as water and air quality, building codes, clean energy, reducing the impacts of polluting industries, and more. For example, the Green Share Garden Project in Lewistown is a nonprofit garden growing organic produce to donate to the community. Volunteers at Glendive Recycles Our Waste (GROW) work to educate their community about recycling, and collect and process recyclables in order to divert waste from the landfill, with the intent to reduce landfill expansion that could be costly to the local taxpayers.

When we consider statewide policy at MEIC, we work with our members across the state to elevate solutions that work for everyone while protecting air, water and healthy landscapes. While it’s clear that there is no single, perfect, one-size-fits-all solution to the real challenges we share across Montana, our current state administration continues to undermine local concerns and minimize public participation in favor of industry-friendly state-level policy to govern all of Montana. We at MEIC are concerned that this behavior will dominate the conversations and policy-making around clean energy, housing, sustainable planning, and water availability.

Lewistown’s nonprofit garden provides fresh produce for community members.

Lewistown’s nonprofit garden provides fresh produce for community members.

This article was published in the September 2022 issue of Down To Earth.