![]() By Laura Collins

By Laura Collins

The fight against climate change requires a fundamental shift in how cities are designed and regulated. Prioritizing walkability, housing abundance, and transit investment can significantly reduce car reliance and curb emissions at scale. UC Berkeley’s Cool Climate Network has said that infill housing is the “single most impactful measure” that cities could take to reduce emissions. Urban sprawl, a pattern that increasingly characterizes Montana’s development, is one of the most significant contributors to carbon emissions. Ensuring housing availability within existing cities can reduce emissions and make transportation more accessible, but many cities have struggled to address housing reform despite critical shortages. Thus, some state governments, including Montana, are beginning to intervene with state-level zoning reform policy.

One of the primary reasons sprawling development is bad for our climate is the increased dependence on vehicle travel. Greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, particularly from single-occupancy vehicles, lie at the heart of the climate crisis. Nova Scotia’s Dalhousie University estimates that suburban households emit roughly double the carbon emissions of urban households on average, due to both longer driving distances and larger homes. However, it’s not always a choice that pushes people to drive as much as they do; the built environment overwhelmingly favors car dependency. Suburban environments that over-rely on automobiles continue to be expanded, and alternative transportation infrastructure for bikes or buses remains undersupported. California’s SB 375, the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act, recognizes the relationship between the built environment and car dependency. Aiming to curb urban sprawl, reduce vehicle miles traveled, and prioritize alternative transportation modes to decrease greenhouse gas emissions, the act sets a precedent for future policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions through sustainable urban planning and increased density.

Public misconceptions about what urban density means can also pose a challenge to both housing reform and reducing car dependency. When medium-density housing is prohibited across many neighborhoods of a city, high-density housing is often forced into small sections of the city to meet demands. This artificially inflates land costs, sentences neighborhoods to become unwalkable islands, and perpetuates the misconception that urban density is inherently harmful to quality of life and community character. This perception often leads to opposition to zoning changes that could allow for a more sustainable urban landscape, even without dramatic changes to streetscape or skyline.

While many environmentalists understand the connections between climate, mobility, and housing, they may not actively campaign for housing reform. If we are truly serious about tackling the climate crisis, we must also commit to solving the housing crisis — sustainably.

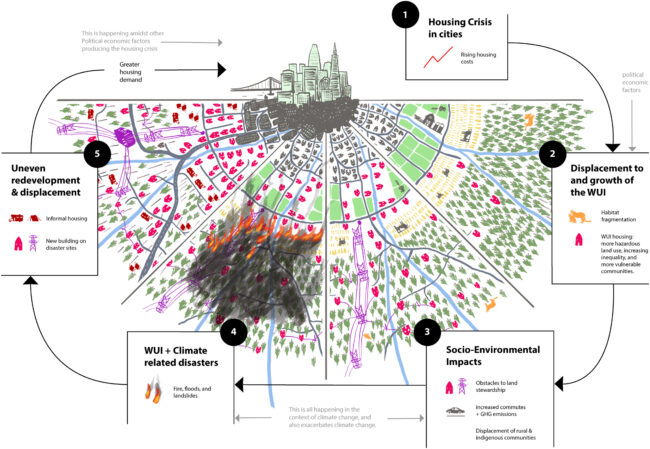

Image via PNAS.

This article was published in the March 2025 issue of Down To Earth.