By Katy Spence

In the 2021 Legislature, which was full of nasty bills, some Helena valley residents had personal connections with two hotly contested, but poorly-publicized, ones:

- HB 599 (Rep. Steve Gunderson, R-Libby) rewrote opencut (i.e., gravel pit) mining laws to the detriment of local citizens.

- HB 527 (Rep. Fiona Nave, R-Columbus) reduced the ability for impacted citizens and local governments to place reasonable conditions on gravel operations.

In 2019, a neighborhood coalition in the Helena valley, then called the Open Pit Group, began to defend its neighborhood against a proposed opencut operation slated for a large swath of unused land. The group used public participation opportunities in the opencut mining laws as they existed at the time, as well as citizen-initiated zoning (CIZ) to create a residential zoning district with regulations to exclude industrial mining operations. With the passage of these bills in 2021, it’s unlikely that other communities will be able to protect their property and water resources as effectively by using the same approach to defeat neighboring opencut mines.

The Battle

After learning in June 2019 of a proposed opencut mine on 61.5 acres of the 70-acre pasture centrally located in his neighborhood, Archie Harper knew the community had limited time to act. The opencut mine proponent presented his plans to the Valley Floodplain Committee at its regular meeting that month. As a member of that committee, Archie realized that his neighbors had no idea what was being planned for the middle of their neighborhood. The land had originally been sold and slated for housing development, but the new owner filed a permit for an opencut mine. At the time, more than 600 residents lived within a half-mile of the site. Of those, approximately 50 homes were directly adjacent to the proposed boundary of the opencut mine. Two of those homeowners were Marty Stebbins and Bob Grudier.

Archie rallied his neighbors, starting a months-long process whose purpose was “to preserve and protect the area’s groundwater resources; minimize flood risk; and promote the residential character of the area, while enhancing the aesthetic character, property values, public health, safety, and welfare of the area.”

Initially known as the Open Pit Group, Archie and his neighbors executed a two-pronged approach to fight the gravel pit: 1) members participated in the proposed permit’s public process overseen by Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and encouraged their neighbors to join, and 2) they pursued a CIZ district to preserve the area’s residential character and the associated agricultural uses.

A CIZ is a community-led process in which the majority of landowners in an area work together to propose zoning an area in their collective interests. Before 2021, the process was meant to help communities determine what they wanted their neighborhood to look like, including the ability to place reasonable conditions on gravel pit operations. The Open Pit Group wanted a neighborhood that allowed urban and suburban residential development, as well as existing agricultural uses, but no mining. In order to submit a CIZ application, the group needed to establish a boundary of the area, get signatures from 60% of the property owners in the area, and raise $500 for the application fee. They did so in just weeks.

Marty Stebbins and Bob Grudier purchased their home in the Helena Valley in the middle of this process. They were warned that the home they bought could soon have a neighboring gravel pit.

“At the time, I thought, ‘What’s a gravel pit?’” Bob said. He had no idea that he’d soon be testifying at the legislature about opencut mining laws.

As the CIZ process moved forward, DEQ finished reviewing the mine permit. In order for the neighborhood to have a chance to give public comment, people living in it had to collect signatures from 30% of the neighboring landowners to request a public meeting. Once again, they rallied.

In early 2020, the Open Pit Group became the West Valley Citizen Alliance Network. The Network rallied the neighbors to attend a February public meeting and voice their concerns. Several hundred homeowners attended the DEQ meeting to provide comments. Archie invoked the Montana Constitution’s guarantee to “a clean and healthful environment,” and a local hydrologist provided research about the imminent dangers to the water quality. Others noted septic impacts, noise and air pollution, road degradation, public safety, and exacerbated flood impacts in a neighborhood already at risk of frequent flood events.

After the meeting, DEQ extended the review period to assess the residents’ numerous and legitimate concerns. In its deficiency notice to the mining company, DEQ said the application did not “adequately protect the local groundwater and surface water resources” or “make adequate provisions for noise and visual impacts on nearby residents.”

DEQ deemed the application “deficient” in May 2020, which meant that the company did not adequately provide solutions to public criticisms brought forth during the review period. In October 2020, the Lewis and Clark County Commission voted to adopt the proposed CIZ, and by July 2021, DEQ officially deemed the opencut mine application “abandoned and void.”

The neighborhood residents want to see the 70-acre open parcel become public property via open space initiatives and, one day, a park to benefit the growing population in the area.

2021 Legislature

Following their victory against the proposed opencut mine, Archie, Marty, and Bob commented and sent messages during the 2021 Legislative Session on HB 599 and HB 527. It’s not that they’re against gravel – far from it.

“We need gravel, just like we need the products of mining,” Marty said. “It’s more of balancing the needs of the Montana people, nature, our whole ecology to make sure that our grandchildren have a healthy environment and also have the materials they need to live in that healthy environment.”

While the West Valley Citizen Alliance Network was successful in using the CIZ tool and public participation allowed by the old version of the opencut mining laws, it was not an easy or straightforward process. And despite these tools being essential in the fight for community self-determination, Gov. Gianforte signed both HB 599 and HB 527 into law at the end of the legislative session.

HB 599 eliminated DEQ’s authority to limit noise, hours of operation, water runoff, fire mitigation, and in many instances, public participation. Developers will be able to classify their own operations as “dry” and DEQ will only have 20 days to issue a permit.

This time period isn’t long enough to allow for a public hearing let alone to allow neighboring landowners to hire experts or have substantive input.

HB 527 reduces the ability of citizens to place reasonable restrictions on gravel pits through CIZs. Specifically, HB 527 states that a CIZ may not prevent the complete use, development, or recovery of any mineral. While “complete use” is still undefined and will need to be hashed out in the courts, it’s clear that the legislative intent of this law was to strip citizens of the ability to adequately plan for an opencut mine moving in next door.

The combination of these new laws makes a repeat of the success in Helena Valley much more difficult for other groups in Montana.

“It was challenging, but it worked,” Archie said. “But they made it even worse, almost to the point where it would make it virtually impossible for local citizens to unite in a timely fashion to head off [a neighboring opencut mine].”

Moving Forward

Marty and Bob said MEIC’s role in helping inform the public played a big role for them during the 2021 Legislative Session and will continue to do so during the rulemaking process for HB 599.

“That’s where MEIC’s mission of making sure information gets out there is really critical, because it was obvious in the last Legislature that our usual ways of getting information out to the public were not happening,” Marty said.

When DEQ starts rulemaking and implementing these new laws, Marty and Bob hope for some more balance and responsibility.

“I think we do have mine owners who are responsible,” Marty said. “But we’re also having to deal with a history of mine owners who are focusing just on taking the resources, and they don’t care about the immediate properties or about what the grandchildren are going to inherit.”

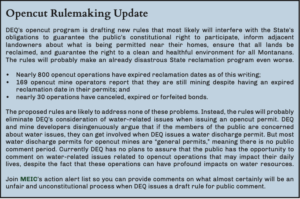

DEQ will soon take the new opencut law through a public rulemaking process and will be looking for input from Montanans. See below.

This article was published in the June 2022 issue of Down To Earth.